It’s not only money what it takes to replace an electronic device

It is hard to live without a smartphone nowadays. We rely on them for every single aspect of our day to day, thus giving it priority over everything else. When our smartphone breaks, stops working or gets lost, we are overcome by a sense of unease, but the solution is easy and quick –buying a new one.

Statistics say that 45 percent of households in the UK have two mobile phones, and one in five have four or more mobile phones. Although talking about smartphones alone in the era of smartwatches, smart bracelets, earbuds, tablets, and voice assistants doesn’t reflect reality –last year every household had an average of 50 connected devices.

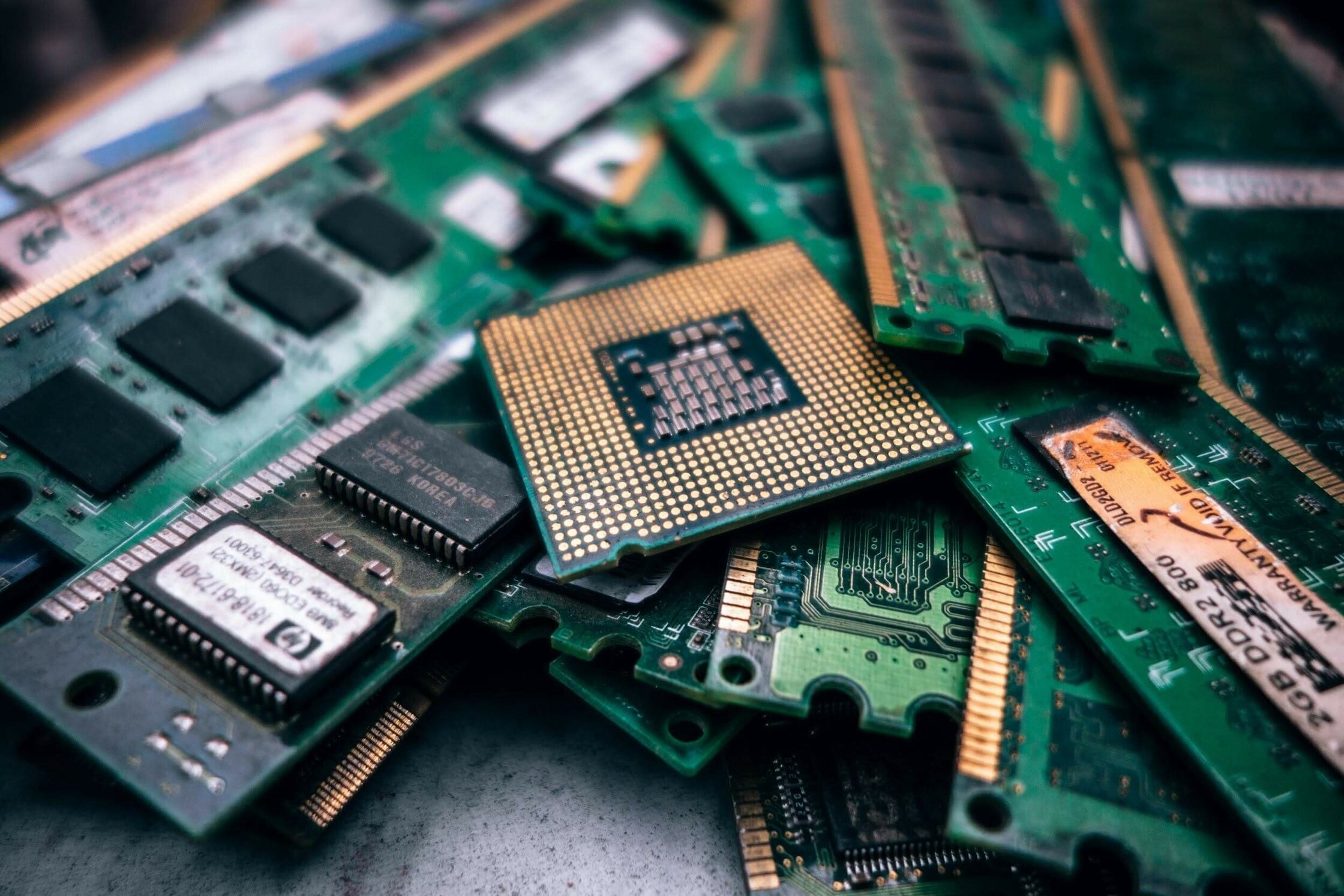

What would we do with those 50 devices in our homes when they start to fail or stop working? Very little people would say they repair them as the tendency, and sometimes the only possibility, is to replace them. We should bear in mind that when using digital tools, there are added environmental and societal costs -when no longer needed, most electronic devices are dumped, not recycled, thus becoming e-waste.

E-waste includes anything with plugs, cords, and electronic components that enters the waste stream. E-waste is extremely dangerous for both the environment and human health. When disposed of in landfills, toxic chemicals, like lead, cadmium or mercury, can leach into the land and water or are released into the atmosphere, and communities living nearby –especially children- may be affected with changes in lung function, respiratory effects, DNA damage and cancer. On the other hand, sometimes the solution to end e-waste is incineration, releasing heavy metals into atmosphere as ashes, as well as gases that attack the ozone layer.

Recycling e-waste is usually a beneficial approach to reuse raw materials in an electronic product, and always a better choice than sending to landfill or incineration. However, there are ethical considerations. Electronic recycling in developed countries takes place in purpose-built plants under controlled conditions, but the process is slow and inefficient. Therefore, e-waste is exported to less developed ones –China, India, the Philippines, Ghana, Nigeria, often in violation of international law, and without the controls that developed countries hold. There, labour laws and safety are more of a myth, and don’t protect those who have to do the demanding and savage work of extracting metals and minerals from e-waste with their bare hands, and who also include children.

Knowing this you’ll be figuring out what to do with unwanted or broken devices to keep them out of landfills and unsustainable recycling. First, ask yourself if you really need to upgrade your device that often. Second, if it’s still working and need minor repair, consider giving it to someone else or donate it to charities that can dismantle every part safely and get value from them. Third, try to return it to the manufacturer or take it to a reliable e-recycling facility.

Nevertheless, this is by no means the job of consumers alone. Solving e-waste is a long-term challenging process that calls for action of all stakeholders involved, such as governments, scientific community, chemical manufacturers, e-product designers and e-recyclers, which need to make sure that the right regulations are implemented and correctly followed by everyone. Only this way we can have an efficient e-waste management and fight against the dangers and inequalities that is currently entailing.